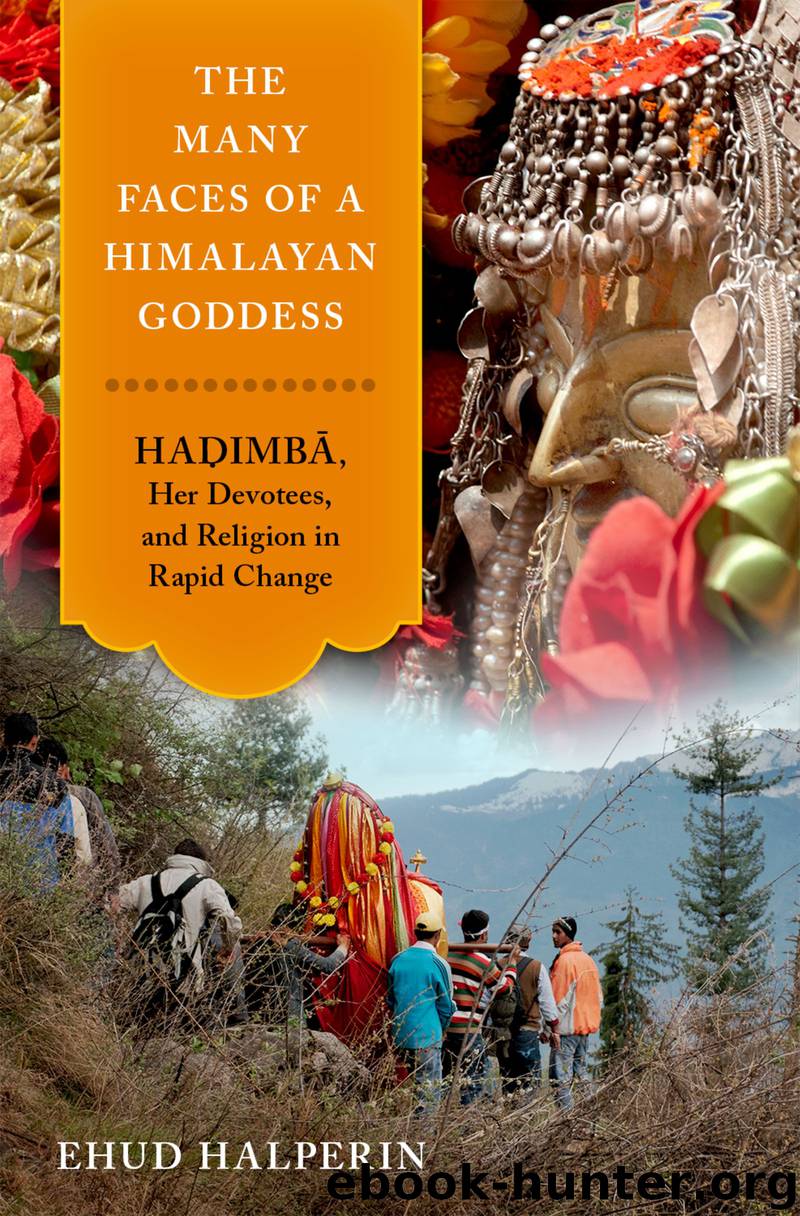

The Many Faces of a Himalayan Goddess by EHUD HALPERIN

Author:EHUD HALPERIN

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Published: 2015-02-24T16:00:00+00:00

Figure 4.1. Ghatotkaca’s tree shrine, Dhungri, 2009. Photo by Ehud Halperin.

The relationship with Ghatotkaca, too, raises difficulties. The connection with the Banjar Ghatotkacas seems to be no more than several decades old. Kamlu remembers how Ghatotkaca’s entourage arrived from Banjar for the first time around the early 1980s: “The devtā [Ghatotkaca from Sidhwa] said he wanted to go to Manali. So [his palanquin and devotees] came down to the Manali school. He then said through his gur that he wanted to go up [to Haḍimbā’s temple]. They have since come to the fair every year.” Furthermore, elders in Manali still call the Dhungri Ghatotkaca so rikhi (Pahari: guardian of the ground). This indicates that he probably used to be a protector deity, whose job was to mark and safeguard the boundary of Haḍimbā’s temple precincts. Neel said that, as a child, he knew Ghatotkaca only as so rikhi. “When things became modern, then people began calling him Ghatotkaca. This happened when the books arrived, when people realized what his real name was, in Sanskrit.” Similarly, Ghatotkaca is not even once mentioned in colonial texts, even in those that identify Haḍimbā as the epic figure Hiḍimbā, suggesting that this devtā was identified as the epic figure rather recently. In oracular sessions, during which Ghatotkaca may be channeled by Haḍimbā’s gur Tuleram or by several other devotees, he expresses himself not in spoken words but with hand gestures. This, locals explain, is because he is dumb (gūṅgā). This fact too contradicts the way he is portrayed in the epic, where he is perfectly capable of speaking aloud.

Additional evidence from around Manali sheds more doubt on the antiquity of local references to the episode about Haḍimbā and Bhim’s love affair. Locals’ accounts of this tale, for example, tend to be extremely thin, in contrast to what we would expect from a narrative tradition that has developed for several centuries. When I asked devotees to tell the story, they simply stated that Haḍimbā married Bhim and mothered Ghatotkaca, but almost never elaborated. They rarely, if ever, mentioned the other Pandava brothers or their mother, Kunti, or gave any details about the fight between Bhim and Haḍimb. When I pressed for further details, they merely suggested that I consult “the books,” where I would find all this itihas (history).20 Those who did have command of the epic narrative, such as Haḍimbā’s head priest Rohitram, drew heavily on common pan-Indian tellings of the epic rather than on any local tradition with its own special twists. Rohitram himself admitted that the Mahabharata tale is essentially different from local stories, though in his eyes this indicates the genuineness of the former in contrast to the imaginary and less authentic status of the latter (Diserens 1993–1994: 114).21

Similarly, as Nisha observed, there is no zikr of Haḍimbā and Bhim’s relationship around Manali. Their story is never told or referred to during local ritual events. Even the traditional devotional song that is performed by local women during Haḍimbā’s birthday festival is silent on this matter.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters(2523)

Kundalini by Gopi Krishna(2168)

Wheels of Life by Anodea Judith(2130)

Indian Mythology by Devdutt Pattanaik(1928)

The Bhagavad Gita by Bibek Debroy(1915)

The Yoga of Jesus: Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels by Paramahansa Yogananda(1843)

Autobiography of a Yogi (Complete Edition) by Yogananda Paramahansa(1805)

The Man from the Egg by Sudha Murty(1797)

The Book of Secrets: 112 Meditations to Discover the Mystery Within by Osho(1656)

Chakra Mantra Magick by Kadmon Baal(1635)

The Sparsholt Affair by Alan Hollinghurst(1578)

Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha(1519)

Sparks of Divinity by B. K. S. Iyengar(1516)

Avatar of Night by Tal Brooke(1511)

Karma-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga by Swami Vivekananda(1486)

The Bhagavad Gita (Classics of Indian Spirituality) by Eknath Easwaran(1470)

The Spiritual Teaching of Ramana Maharshi by Ramana Maharshi(1422)

Hindoo Holiday by J. R. Ackerley(1368)

Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction (Very Short Introductions) by Knott Kim(1363)